Lab 4: Blood

Preparation for lab

To get the most out of this lab you need to be prepared. The basic knowledge needed for this lab is covered in Amerman “Human Anatomy and Physiology” in Chapter 19 “Blood”.

Introduction

Blood, the only fluid connective tissue, consists of plasma and formed elements. While plasma is mostly water with some proteins and dissolved salts, formed elements debelop in the red bone marrow and include red blood cells =RBC, white blood cells, and platelets. Adult males have about 5-6 liters of blood and adult females 4-5 liters. A single drop of blood contains about 260 million red blood cells! This large number is necessary because red blood cells transport Oxygen (O₂ ) to each and every cell in the body. Blood also collects CO₂ and other waste products from the cells, transports nutrients (e.g. glucose), distribute hormones across the body and helps to regulate body temperature.

Do these experiments as a group - i.e. choose one student to take the lead and serve as test subject for each of the sections. Then work through the experiments together with the other student assisting and/or observing.

Hemoglobin (student #1)

Hemoglobin (Hb) is the protein in RBCs responsible for transporting O₂ through the blood. Hb constitutes more than 95% of the non-water content inside RBCs. It has a quaternary protein structure consisting of four globular protein subunits. Each subunit contains an iron atom, which is the site of O₂ binding. When Hb binds O₂ its color is bright red (arterial blood). As O₂ is used in cells and little bound O₂ remains, the blood’s color is rather dark red (or blue if viewed through skin; venous blood). The color of a blood sample can be used to measure the amount of Hb in the blood. This quick and easy test is helpful to e.g. determine if a person suffers from anemia - a condition caused by a deficiency of red blood cells or of hemoglobin in the blood.

DIRECTIONS: When drawing small quantities of blood (a few drops), it is easiest and least painful to do so from the side of the fingertips. Have a paper towel handy to apply pressure against the skin after you obtain the samples for the tests you are performing. Open an alcohol prep pad and wipe the side of a lesser-used fingertip. Press the red tip of the safety lancet against the skin. The lancet will click as its internal needle penetrates the skin and retracts. Squeeze distally along the length of the finger to milk blood out of the wound. Wipe away the first blood that comes out with an alcohol pad. Once you have collected the necessary blood for each test, apply pressure against the wound with a paper towel to stop the bleeding.

To estimate Hb levels, soak a piece of chromatography paper with a drop of blood and allow it to dry. Next, compare the color of the blood spot to the Hemoglobin Color Scale to estimate the Hb content of the blood in g/dl. Normal hemoglobin levels are 12-15 g/dl for women and 14-17 g/dl for men. Could your subject be suffering from anemia?

Hematocrit (student #2)

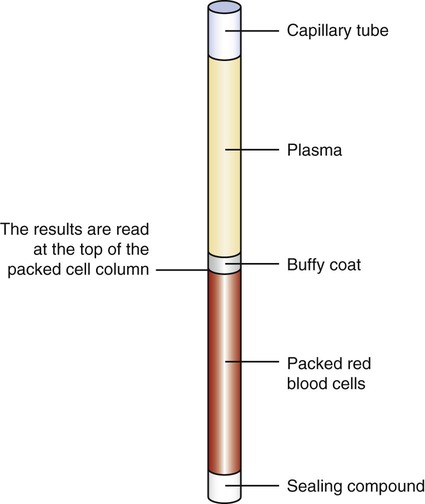

Hematocrit is the percent of blood volume that is occupied by RBCs. It is also called PCV or packed cell volume - which hints at how you determine it. A centrifuge is used to spin a blood sample, causing the heavy RBCs to ’pack’ into the bottom end of the capillary, whereas the the light, clear plasma (water, solutes, and light plasma proteins) stay at the top end. White blood cells and platelets are ’heavier’ than plasma, but not as ’heavy’ as RBCs and thus stay in middle - visible as the so called buffy coat.

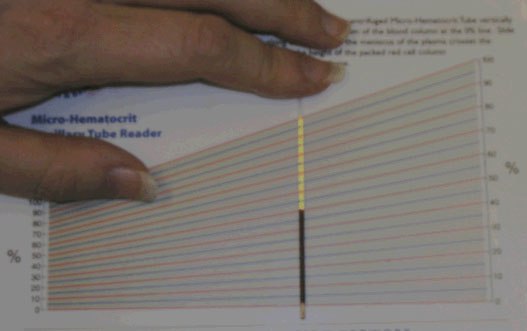

DIRECTIONS: Fill a heparinized (heparin is a chemical that prevents blood form coagulating) capillary tube with a sample of blood (the more you can fill the capillary, the easier it will be to read of the hematocrit and the more precise the test will work!). Plug the bottom of the tube with the white clay found at your bench. Bring the tube to the front of the lab. The instructor will place the tube into the centrifuge and tell you which position in the centrifuge it is in. Once everyone’s sample is in the centrifuge, we will spin the blood at 10,000 RPM for 5 minutes. After the blood has been spun, find your tube and measure the hematocrit. The hematocrit is the % of packed red blood cells compared to the entire capillary content (RBCs, buffy coat, clear plasma). Use a sliding scale to read it! The scale either slides or spins so that the height of the blood sample in your tube can be lined up with the 100% marker on the scale. Normal hematocrit levels are 38% for women and 46% for men. Note your hematocrit. Is it within normal levels? How does it compare with the hemoglobin level you determined through the blood color?

Read of the hematocrit at the top end of the packed RBC (in this example 50%). Note: some sliding scales are designed to rotate.

Reading the hematocrit by sliding it on the scale: Align the bottom end of the packed RBC with the 0% line and the top of the clear portion (the plasma) with the (angled) 100% line.

Blood Sugar Levels (student #3)

Besides the transport of gasses (e.g. O₂ and CO₂ ), blood also transports nutrients to the cells. Humans use the simple sugar glucose as the primary source of energy. Glucose is transported from the intestine or liver (where it is stored as glycogen) to all cells in the body to be ’burned’ by the mitochondria. The body uses the hormone insulin to regulate how much glucose is in the blood stream, the blood glucose level. A persistently low blood glucose level is called hypoglycemia. Persistently high levels are called hyperglycemia and characteristic for the disease Diabetes mellitus. Variations in blood sugar are normal over the course of the day, e.g. the blood sugar level quickly rises when we consume foods with a high Glycemic Index at lunch, however, after a few hours they should return to between 3.9 and 5.5 mmol/L (70 to 100 mg/dL).

DIRECTIONS:

- Insert a test strip into the blood glucose meter. This should turn the meter on. Once the meter has turned on and is ready for a blood sample, touch the test strip to your blood to draw some up onto the test strip. What is your blood glucose level?

- Eat some food with very high gycemic index - candy comes to mind. Wait for ~30 minutes.

- Repeat the blood glucose measurement. How did the value change?

Blood Type (student #4)

RBCs and the Immune System

The Immune System is the body’s defense against bacteria, viruses, or any other substances that ’shoudn’t be’ inside the body. It distinguishes between the body’s own cells and intruders with the help of surface antigens. Specific antigens are attached your cell’s plasma membranes and your immune system, specifically the antibodies, recognize them and leaves these cells alone - just like you would used your student ID to show campus police that you belong here.

Like any other cell type, RBCs have surface antigens, too. This creates a problem when a patient needs a blood transfusion (blood is too complex to artificially synthesize, so modern medicine still relies on blood donors!): If antibodies in the recipient detect the ’wrong’ type of antigen, the patient’s immune system will attack the donor’s blood cells. There are a number of systems we use to ensure that blood is ’compatible’, i.e. the antigens and antibodies are similar enough between two individuals for their immune systems not to attack the other’s RBCs. Similar types of blood are grouped into blood groups, i.e. Type AB. The two most commonly grouping systems are the ABO and the Rhesus (Rh) system.

The ABO system distinguishes between four groups:

-

Type A: cells with Antigen A and blood with with Antibody B (22.88% of population)

-

Type: B: cells with Antigen B and blood with with Antibody A (32.26%)

-

Type AB: cells with Antigen AB, blood has no Antibodies (7.74%)

-

Type O or 0[^1]: cells have no Antigen, blood has Antibodies A and B (37.12%)

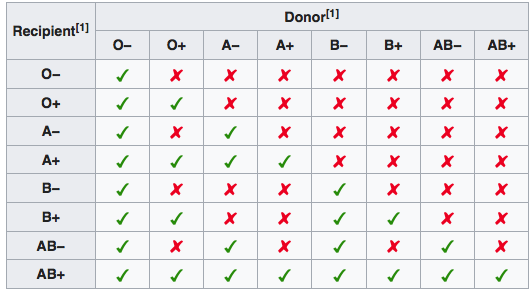

Table summarizing blood compatibility according to the AB0 and Rh systems. There is still the possibility that atypical antibodies are present that could cause an incompatibility.

As e.g. the cells of a person with blood type B have antigens of the type ’B’, but the blood doesn’t contain and ’B’ antibodies, so no immune reaction happens. Should this person, however, receive a blood donation from donor with blood type A, cells with antigen ’A’ are suddenly introduced and react with the ’A’ antibodies in the blood. When ’A’ antigens and antibodies encounter each other, they bind and neutralize (coagulate) the RBCs. Test yourself: Can a patient with blood type B receive blood from a donor with blood type AB? What about a donor with blood type 0? In transfusions individuals with type O Rh D negative blood are often called universal donors. Those with type AB Rh D positive blood are called universal recipients.

The Rhesus (Rh) system just looks for presence of anti-D antibodies[^2]: if a patient does not have any she is Rh D-negative, if she does, she is Rh D-positive. If you don’t have anti-D antibodies (Rh-D negative), you can only receive blood donations from donors that are also Rh-negative. If you are Rh D-positive, it doesn’t matter.

DIRECTIONS: Place a drop of simulated blood (which contains RBC with a subjects antigens) in each of the three wells of the plastic test slide. The instructor will provide a drop of anti-A, anti-B, and anti-Rh antibodies. Use a toothpick and gently mix the blood and the antibody solution. Use a clean toothpick for each of the three wells to prevent cross-contamination of the antibodies! Wait about a minute, gently rocking the test slide back and forth. Look for agglutination (formation of little clumps). If you see agglutination, you possess that antigen. Don’t wait too long - after 10-15 minutes all samples will look dried-in and agglutinated! What is your blood type?

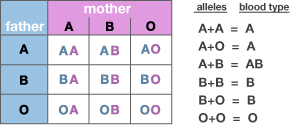

Blood type inheritance

What determines your blood type? Genetics - Antigen and Antibody types are inherited from your parents. Each parent contributes one of their two ABO alleles on chromosome 9. A parent with blood type AB can pass on either the A allele, or the B allele. If you inherit one O allele and one A (or B) allele, your blood type is A (or B). Thus, the only way for you to have blood type O is to inherit an O allele from your mother and your father. This test isn’t fail-safe: other blood groups than the ABO give misleading results and e.g. the Bombay phenotype and cis-AB lead to a type O child being born to an AB parent.

Table with possible combinations of blood type alleles. Due to the simplification of the blood type system, blood groups are only about 40% effective to rule out a man as a child’s potential father. Modern laboratory tests use genetic methods for a more reliable test.

Hemolytic disease of newborns

As the father contributes one allele determining the fetuses blood type, it is possible for a fetus to have a blood type that is incompatible with that of the mother. The mother’s and fetus’s blood circulation are mostly separated by the placenta. If, however, the mother’s blood gets exposed to the fetuses’s blood (e.g. due to complications during pregnancy or at birth ), the mother’s immune system will form antibodies against the fetus’s RBCs. This can cause Rh disease or other forms of hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) in the current pregnancy and/or subsequent pregnancies. Sometimes this is lethal for the fetus. If a pregnant woman is known to have anti-D antibodies, the Rh blood type of a fetus can be tested by analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma to assess the risk to the fetus of Rh disease. Modern medicine has developed Rho(D) immune globulin (trade name RhoGAM) which can prevent the formation of Anti-D antibodies by D negative mothers when given during pregnancy. Under what scenario could this affect you?

Setup & supplies

For each table

-

safety Lancets

-

alcohol wipes

-

blotting paper

-

Hemoglobin Color Scale booklet

-

heparinized capillary tubes

-

glucose test strips

-

glucose meter

-

clay

-

plastic test slide

-

tooth picks

For the lab

-

centrifuge

-

hematocrit reader

-

anti-A, anti-B, anti-Rh antibodies